Have you ever encountered an image that made you pause, stare longer than usual, and question what you were seeing? Those moments reveal just how fragile our sense of visual certainty truly is. We like to believe that our eyes transmit reality faithfully, but in truth, vision is a collaborative effort between the eyes and the brain. The brain constantly interprets, fills in gaps, and prioritizes speed over accuracy, allowing us to respond quickly to potential threats or opportunities. However, this efficiency can become a weakness when confronted with unusual angles, deceptive lighting, or perfectly timed snapshots. A photograph freezes a fleeting moment, stripping away motion, depth, and context. This forces the brain to guess, and it doesn’t always guess correctly. That split-second pause—the hesitation before understanding—is the mind recognizing that its first interpretation may have been flawed. The experience is both unsettling and fascinating, demonstrating that perception is not a passive reception of reality but an active, interpretive process.

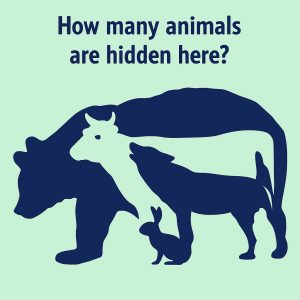

Human perception evolved to detect patterns rapidly, a survival mechanism that often serves us well but can also mislead. Our brains are constantly searching for familiar shapes—faces, animals, objects—because recognizing them quickly once meant the difference between safety and danger. This pattern-seeking tendency explains phenomena like seeing faces in clouds, animals in shadows, or human figures in random arrangements of objects. Psychologists call this pareidolia, and it plays a key role in why certain images appear strange or deceptive. When a photograph contains ambiguous forms or incomplete information, the brain rushes to impose meaning based on past experiences, filling in missing details before conscious analysis. Shadows may appear solid, reflections may seem tangible, and ordinary items may transform into something entirely different depending on perspective or lighting. These perceptual shortcuts usually aid survival, but in photography, they are often exploited, turning mundane scenes into visual puzzles that challenge our confidence in what we see.

What makes these illusions so compelling is the initial certainty we place in our interpretations. At first glance, an image may appear straightforward, with no apparent anomalies, prompting our brains to quickly assert understanding. Only after a second or third look does the illusion unravel: an animal is merely a shadow, a threatening scene is benign, or a body part belongs to someone entirely different. This correction process can provoke amusement, surprise, or mild alarm, emphasizing how much of what we “see” is assumption rather than observation. Human recognition is rapid but often lazy, relying on shortcuts instead of careful analysis. In a fast-paced world, we rarely practice the patience needed for deliberate observation, but these deceptive images force us to slow down, challenge initial impressions, and reconsider how perception works. They reveal that seeing is not synonymous with understanding, and that true observation requires effort and attention.

Perspective and timing are the primary tools that deceptive images exploit. Perspective can flatten depth, making distant objects seem enormous or nearby ones vanish, creating impossible visual alignments. A person standing far behind another can appear gigantic, or objects can appear fused with people’s bodies in improbable ways. Timing compounds this effect: a photograph captures a fraction of a second, often isolating an event that makes little sense without the frames before or after. A jumping dog may look like it’s suspended midair, a splash of water may resemble smoke or fire, or a hand mid-motion may seem detached. These illusions exploit the brain’s expectation of continuity and motion, highlighting the gap between dynamic reality and the static image. Our perceptual system anticipates patterns, yet photographs freeze a single moment, leaving the brain momentarily confused. The resulting tension between expectation and observation is what makes such images both fascinating and memorable.

Emotional response plays a critical role in our interpretation of deceptive images. Some images provoke laughter once the illusion is revealed, while others induce a brief surge of fear or discomfort before logic intervenes. A shadow might momentarily resemble a lurking animal, or a strangely shaped object might appear ominous. These reactions occur because the brain processes emotional cues faster than rational analysis. Before conscious understanding occurs, the nervous system may already respond, triggering what feels like an instinctive reaction—an emotional whiplash of confusion followed by clarity. This immediate, visceral response is part of the appeal of such images, creating a condensed narrative of surprise, realization, and amusement in just a few seconds. The memory of that brief emotional rollercoaster often makes the images highly shareable, reinforcing our fascination with perceptual illusions and the brain’s interpretive quirks.

Ultimately, deceptive images do more than entertain; they offer insight into the mechanisms of human perception. In a world saturated with visuals, we often glance rather than look, assume rather than analyze. These images invite careful observation, urging us to question first impressions and engage deeply with the information before us. They remind us that context matters, that certainty is rarely absolute, and that perception is a blend of assumption, interpretation, and inference. By slowing down and examining details, we not only uncover hidden truths in images but also gain understanding of our cognitive processes, the shortcuts our brains employ, and the assumptions we make. In doing so, we realize that reality is rarely as straightforward as it seems, and the most revealing moments often occur when our confidence in what we see quietly collapses, leaving space for curiosity, insight, and awe.