Our perception of the world is not always as reliable as we assume. Optical illusions demonstrate that our eyes and brains can be tricked by patterns, light, and context, creating images that appear different from reality. From everyday encounters to curated visual media, these illusions challenge the notion that seeing is believing. Viral Strange and similar platforms highlight images that compel viewers to look twice, revealing hidden shapes, unusual perspectives, or clever manipulations of color and light. These moments remind us that perception is an active process—our brains interpret, infer, and sometimes misinterpret the visual information received from our eyes.

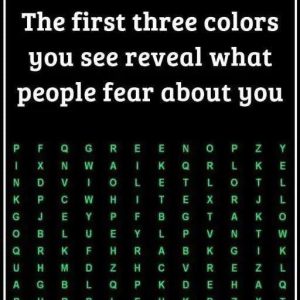

One common type of optical illusion relies on ambiguous figures, where a single image can be perceived in multiple ways depending on focus or perspective. These images often conceal one object within another, forcing the viewer to shift attention to grasp the full picture. The brain tends to favor the most obvious interpretation first, which explains why some illusions require repeated viewing. By pausing, adjusting focus, or considering different angles, hidden details emerge, creating an “aha” moment that reveals the complexity of human perception. This process not only entertains but also provides insight into how the mind prioritizes visual input.

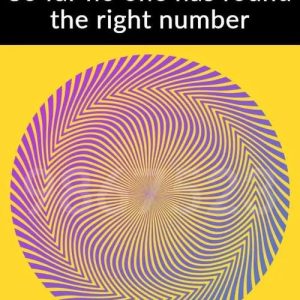

Another category of visual trickery involves illusions based on size, proportion, or spatial relationships. Lines, angles, and shapes can be arranged to create the impression of movement, depth, or distortion, even though the physical image is static and two-dimensional. These effects exploit the brain’s reliance on context cues and prior knowledge to interpret the world. Everyday examples might include buildings that appear to lean, roads that seem longer than they are, or objects that seem to bend or twist in impossible ways. Recognizing these patterns enhances critical observation skills and highlights the limitations of our visual assumptions.

Visual misinterpretation is not limited to illusions; it extends to art as well. Styles with similar characteristics or names can confuse even seasoned observers. By training attention to specific features—brush strokes, color palettes, thematic focus, and compositional elements—viewers can learn to differentiate between artistic movements or individual artists. For instance, distinguishing impressionism from post-impressionism requires noticing subtleties in technique and subject portrayal. Developing this level of visual literacy deepens appreciation for art while sharpening perceptual acuity, enabling a more informed and enriched experience of both art and everyday visuals.

The study of optical illusions also intersects with science, psychology, and neuroscience. Researchers investigate why and how certain images trick the brain, exploring the mechanisms behind visual perception, pattern recognition, and cognitive bias. Some illusions reveal universal tendencies in human cognition, while others are culturally or experientially influenced. By examining how the brain processes contradictory or ambiguous information, scientists can better understand attention, memory, and decision-making processes. Additionally, this research informs practical applications, such as design, safety, and education, by revealing how visual cues influence perception and behavior.

In conclusion, optical illusions serve as a compelling reminder that our eyes and brain do not always convey reality perfectly. They challenge assumptions, promote critical observation, and highlight the active role of cognition in perception. Whether in everyday life, art appreciation, or scientific study, illusions encourage us to slow down, examine details, and embrace curiosity about how we see the world. Platforms like Viral Strange showcase images that stimulate this exploration, prompting viewers to question initial impressions and discover hidden depths. Ultimately, understanding illusions enhances visual literacy, enriches engagement with our environment, and reminds us of the fascinating complexity behind even the simplest act of seeing.